Introduction To The Study Of The Ten Sefirot Pdf Writer

Zohar - Wikipedia. The Zohar (Hebrew:. The Zohar contains discussions of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and. Introduction To The Study Of The Ten Sefirot Pdf Writer. Its scriptural exegesis can be considered an esoteric form of. This is because there have already been incidents of deviation from the path of Torah because of engagement in Kabbalah. Hence, “Why do I need this trouble? Who is so foolish as to place himself in danger for no reason?” Fourth: Even those who favor this study permit it only to holy ones, servants of the Creator.

The tetragrammaton in (10th century BCE to 135 CE), old (10th century BCE to 4th century CE) and square (3rd century BCE to present) scripts The tetragrammaton (; from Τετραγράμματον, meaning '[consisting of] four letters'), יהוה in Hebrew and YHWH in Latin script, is the four-letter biblical name of the God of Israel. The books of the and the rest of the Hebrew Bible (with the exception of,, and ) contain the Hebrew word יהוה.

Religiously observant and those who follow conservative Jewish traditions do not pronounce יהוה, nor do they read aloud transliterated forms such as; instead the word is substituted with a different term, whether used to address or to refer to the God of Israel. Common substitutions for Hebrew forms are hakadosh baruch hu ('The Holy One, Blessed Be He'), ('The Lord'), or ('The Name'). Transcription of the divine name as ΙΑΩ in the 1st-century BCE The letters YHWH are consonantal semi-vowels. In unpointed Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as certain consonants can double as vowel markers (similar to the use of V to indicate both U and V).

These are referred to as ('mothers of reading'). Therefore, it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced only from its spelling, and the tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced. Thus the first-century Jewish historian and philosopher said that the sacred name of God consists of 'four vowels'.

The original of the Hebrew Bible was, several centuries later, provided with vowel marks by the to assist reading. In places that the consonants of the text to be read (the ) differed from the consonants of the written text (the ), they wrote the qere in the margin as a note showing what was to be read. In such a case the vowels of the qere were written on the ketiv. For a few frequent words, the marginal note was omitted: these are called. One of the frequent cases was the tetragrammaton, which according to later Jewish practices should not be pronounced but read as ' ('My Lord'), or, if the previous or next word already was, as ' ('God'). The combination produces יְהֹוָה and יֱהֹוִה respectively, that would spell 'Yehovah' and 'Yehovih' respectively.

The oldest complete or nearly complete manuscripts of the with, such as the and the, both of the 10th or 11th century, mostly write יְהוָה ( yhwah), with no pointing on the first h. It could be because the o diacritic point plays no useful role in distinguishing between Adonai and and so is redundant, or it could point to the qere being Shema, which is for 'the Name'. The spelling of the tetragrammaton and connected forms in the Hebrew Masoretic text of the Bible, with shown in red The vocalisations of יְהֹוָה ( Yehovah) and אֲדֹנָי ( Adonai) are not identical. The in YHWH (the vowel 'ְ ' under the first letter) and the in 'DNY (the vowel 'ֲ ' under its first letter) appear different. The vocalisation can be attributed to Biblical Hebrew phonology, where the hataf patakh is grammatically identical to a shva, always replacing every under a. Since the first letter of אֲדֹנָי is a guttural letter while the first letter of יְהֹוָה is not, the hataf patakh under the (guttural) reverts to a regular shva under the (non-guttural). The table below considers the vowel points for יְהֹוָה ( Yehovah) and אֲדֹנָי ( Adonai), respectively: Hebrew word No.

3068 YEHOVAH יְהֹוָה Hebrew word No. 136 ADONAY אֲדֹנָי י Yod Y א Aleph ְ Simple Shewa e ֲ Hataf Patakh A ה Heh H ד Daleth D ֹ Holem O ֹ Holem O ו Waw W נ Nun N ָ Kametz A ָ Kametz A ה Heh H י Yod Y In the table directly above, the 'simple shewa' in Yehovah and the hataf patakh in Adonai are not the same vowel. The difference being, the 'simple shewa' is an 'a' sound as in 'alone', whereas the hataf patakh is more subtle, as the 'a' in 'father'. The same information is displayed in the table above and to the right, where YHWH is intended to be pronounced as Adonai, and Adonai is shown to have different vowel points. Tetragrammaton (with the vowel points for Adonai) on a Wittenberg University debate lectern The Hebrew scholar [1786–1842] suggested that the Hebrew punctuation יַהְוֶה, which is transliterated into English as ', might more accurately represent the pronunciation of the tetragrammaton than the Biblical Hebrew punctuation ' יְהֹוָה', from which the English name 'Jehovah' has been derived. His proposal to read YHWH as ' יַהְוֶה' (see image to the left) was based in large part on various Greek transcriptions, such as ιαβε, dating from the first centuries CE but also on the forms of theophoric names. In his Hebrew Dictionary, Gesenius supports 'Yahweh' (which would have been pronounced [jahwe], with the final letter being silent) because of the Samaritan pronunciation Ιαβε reported by, and that the prefixes YHW [jeho] and YH [jo] can be explained from the form 'Yahweh'.

Gesenius' proposal to read YHWH as יַהְוֶה is accepted as the best scholarly reconstructed vocalised Hebrew spelling of the tetragrammaton. Theophoric names [ ]. Leningrad Codex [ ] Six Hebrew spellings of the tetragrammaton are found in the of 1008–1010, as shown below. The entries in the Close Transcription column are not intended to indicate how the name was intended to be pronounced by the Masoretes, but only how the word would be pronounced if read without. Chapter and verse Hebrew spelling Close transcription Ref. Explanation Genesis 2:4 יְהוָה Yǝhwāh This is the first occurrence of the tetragrammaton in the Hebrew Bible and shows the most common set of vowels used in the Masoretic text. It is the same as the form used in Genesis 3:14 below, but with the dot over the holam/waw left out, because it is a little redundant.

Genesis 3:14 יְהֹוָה Yǝhōwāh This is a set of vowels used rarely in the Masoretic text, and are essentially the vowels from Adonai (with the hataf patakh reverting to its natural state as a shewa). Judges 16:28 יֱהֹוִה Yĕhōwih When the tetragrammaton is preceded by Adonai, it receives the vowels from the name Elohim instead. The hataf segol does not revert to a shewa because doing so could lead to confusion with the vowels in Adonai. Genesis 15:2 יֱהוִה Yĕhwih Just as above, this uses the vowels from Elohim, but like the second version, the dot over the holam/waw is omitted as redundant. 1 Kings 2:26 יְהֹוִה Yǝhōwih Here, the dot over the holam/waw is present, but the hataf segol does get reverted to a shewa.

Ezekiel 24:24 יְהוִה Yǝhwih Here, the dot over the holam/waw is omitted, and the hataf segol gets reverted to a shewa. Ĕ is hataf; ǝ is the pronounced form of plain. The o diacritic dot over the letter is often omitted because it plays no useful role in distinguishing between the two intended pronunciations Adonai and Elohim (which both happen to have an o vowel in the same position).

Dead Sea Scrolls [ ] In the and other Hebrew and Aramaic texts the tetragrammaton and some other (such as El or Elohim) were sometimes written in, showing that they were treated specially. Most of God's names were pronounced until about the 2nd century BCE.

Then, as a tradition of non-pronunciation of the names developed, alternatives for the tetragrammaton appeared, such as Adonai, Kurios and Theos. The, a Greek fragment of Leviticus (26:2–16) discovered in the Dead Sea scrolls (Qumran) has ιαω ('Iao'), the Greek form of the Hebrew trigrammaton YHW.

The historian (6th century) wrote: 'The Roman [116–27 BCE] defining him [that is the Jewish god] says that he is called Iao in the Chaldean mysteries' (De Mensibus IV 53). Van Cooten mentions that Iao is one of the 'specifically Jewish designations for God' and 'the Aramaic papyri from the Jews at Elephantine show that 'Iao' is an original Jewish term'. The preserved manuscripts from Qumran show the inconsistent practice of writing the tetragrammaton, mainly in biblical quotations: in some manuscripts is written in paleo-Hebrew script, square scripts or replaced with four dots or dashes ( tetrapuncta). The members of the Qumran community were aware of the existence of the tetragrammaton, but this was not tantamount to granting consent for its existing use and speaking. This is evidenced not only by special treatment of the tetragrammaton in the text, but by the recommendation recorded in the 'Rule of Association' (VI, 27): 'Who will remember the most glorious name, which is above all [.]'. The table below presents all the manuscripts in which the tetragrammaton is written in paleo-Hebrew script, in square scripts, and all the manuscripts in which the copyists have used tetrapuncta. Copyists used the 'tetrapuncta' apparently to warn against pronouncing the name of God.

In the manuscript number 4Q248 is in the form of bars. Tetragrammaton written in script on 8HevXII The oldest complete (B, א, A) versions from fourth century onwards consistently use Κύριος ('), or Θεός ('), where the Hebrew has YHWH, corresponding to substituting Adonai for YHWH in reading the original. The use of Κύριος for translating YHWH was not common in LXX mss before that time. In books written in Greek in this period (e.g., Wisdom, 2 and 3 Maccabees), as in the, Κύριος takes the place of the name of God. However, the oldest fragments had the tetragrammaton in Hebrew or Paleo-Hebrew characters, with the exception of (perhaps the oldest extant manuscript) where there are blank spaces, leading some scholars such as to believe that it contained letters. According to, the tetragrammaton must have been written in the manuscript where these breaks or blank spaces appear. Albert Pietersma claim that P.

458 is not important for their discussion of tetragrammaton, but he mentions it for ancient and for one surmise, since, all the contemporary ancient manuscripts present any form of divine name. Other oldest fragments of manuscripts cannot be used in discussions because, in addition to its small text and its fragmentary condition, it does not include any Hebrew Bible verses where the Tetragrammaton appears (i.e.,,, ). The claim that 4Q126 has Κύριος is implausible, because its text is unidentified, appearing this title (Kyrios) replacing the divine name from the third century onwards (i.e. P.Oxy656, P.Oxy1075 and P.Oxy1166). 4Q126 is not considered a biblical manuscript. Throughout the Septuagint as now known, the word Κύριος ( Kyrios) without the definite article is used to represent the divine name, but it is uncertain whether this was the Septuagint's original rendering.

( Commentary on Psalms 2.2) and ( Prologus Galeatus) said that in their time the best manuscripts gave not the word Κύριος but the tetragrammaton itself written in an older form of the Hebrew characters. No Jewish manuscript of the Septuagint has been found with Κύριος representing the tetragrammaton, and it has been argued, not altogether convincingly, that the use of the word Κύριος shows that the Septuagint as now known is of Christian character, and even that the composition of the New Testament preceded the change to Κύριος in the Septuagint. The use of Κύριος throughout to represent the tetragrammaton has been called 'a distinguishing mark for any Christian LXX manuscript'. However, a passage recorded in the Hebrew, Shabbat 13:5 (written c. 300 CE), quoting (who lived between 70 and 135 CE) is sometimes cited to suggest that early Christian writings or copies contained the Tetragrammaton.

In earliest copies of the Septuagint, the tetragrammaton in either Hebrew or paleo-Hebrew letters is used. The tetragrammaton occurs in the following texts: • – contains fragments of Deuteronomy. Has blank spaces where the copyist probably had to write the tetragrammaton. It has been dated to 2nd century BCE. • (848) – contains fragments of Deuteronomy, chapters 10 to 33, dated to 1st century BCE.

Apparently the first copyist left a blank space and marked with a dot, and the other inscribed letters, but not all scholars agree to this view. • – contains chapter 42 of the Book of Job and the tetragrammaton written in paleo-Hebrew letters. It has been dated to the 1st century BCE. • – dated to the 1st century CE, includes three fragments published separately. • has Tetragrammaton in 1 place • in 24 places, whole or in part. • in 4 places. • – contains fragments of the Book of Psalms.

It has been dated between year 50 and 150 CE • – contains fragments of the Book of Leviticus, chapters 1 to 5. In two verses: 3:12; 4:27 the tetragrammaton appears in the form ΙΑΩ. This manuscript is dated to the 1st century BCE. • – containing fragments of the Book of Genesis, chapters 14 to 27. A second copyist wrote Kyrios. It is dated to the late 2nd or early 3rd century CE.

• – this manuscript in vitela form contains Genesis 2 and 3. The divine name is written with a double. It has been assigned palaeographically to the 3rd century. • – containing fragments of the Book of Genesis, chapter 19. Contains a blank space for the name of God apparently, although Emanuel Tov thinks that it is a free space ending paragraph. It has been dated to 3rd century CE. • Taylor-Schechter 16.320 – tetragrammaton in Hebrew, 550 – 649 CE.

• – has the divine name on marginal notes in Greek letters ΠΙΠΙ, and is the only another mss. It is a 6th-century Greek manuscript. • – a Hexapla manuscript with tetragrammaton in Greek letters ΠΙΠΙ. It is from 7th-century.

• – the latest Greek manuscript containing the name of God is, transmitting among other translations the text of the Septuagint. This codex comes from the late 9th century, and is stored in the. In some earlier Greek copies of the Bible translated in the 2nd century CE by and, the tetragrammaton occurs.

The following manuscripts contain the divine name: •, the P.Vindob.G.39777 – dated to late 3rd century or beginning 4th century. •, this is a Septuagint manuscript dated after the middle of the 5th century, but not later than the beginning of the 6th century. • – a manuscript of the Septuagint dated late 5th century or early 6th century. Sidney Jellicoe concluded that ' is right in holding that LXX [Septuagint] texts, written by Jews for Jews, retained the divine name in Hebrew Letters (paleo-Hebrew or Aramaic) or in the Greek-letters imitative form ΠΙΠΙ, and that its replacement by Κύριος was a Christian innovation'. Jellicoe draws together evidence from a great many scholars (B. Roberts, Baudissin, Kahle and C.

Roberts) and various segments of the Septuagint to draw the conclusions that the absence of 'Adonai' from the text suggests that the insertion of the term Kyrios was a later practice; in the Septuagint Kyrios is used to substitute YHWH; and the tetragrammaton appeared in the original text, but Christian copyists removed it. [ ] and (translator of the ) used the. Both attest to the importance of the sacred Name and that some manuscripts of Septuagint contained the tetragrammaton in Hebrew letters. [ ] This is further affirmed by The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology, which states 'Recently discovered texts doubt the idea that the translators of the LXX (Septuagint) have rendered the tetragrammaton JHWH with KYRIOS. The most ancient mss (manuscripts) of the LXX today available have the tetragrammaton written in Hebrew letters in the Greek text. This was a custom preserved by the later Hebrew translator of the Old Testament in the first centuries (after Christ)' New Testament [ ].

Main article: No Greek of the uses the tetragrammaton.: 77 In all its quotations of Old Testament texts that have the tetragrammaton in Hebrew the New Testament uses the Greek word Κύριος ( ). However, within the New Testament the name that the tetragrammaton represents underlies the of some of the people mentioned (such as and ), and the name appears in the abbreviated form in the Greek phrase Ἁλληλουϊά ( ) in. Tetragrammaton at the Fifth Chapel of the, France. This example has the vowel points of '. According to the (1910) and B.D. Eerdmans:: 330 • (1st century BCE) writes Ἰαῶ (Iao); • (d. 202) reports that the Gnostics formed a compound Ἰαωθ (Iaoth) with the last syllable of.

He also reports that the use Ἰαῶ (Iao); • (d. 215) writes Ἰαοὺ (Iaou)—see also below; • (d. 254), Ἰαώ (Iao); • (d. 305) according to (died 339), Ἰευώ (Ieuo); • (died 404), who was born in Palestine and spent a considerable part of his life there, gives Ἰά (Ia) and Ἰάβε (Iabe) and explains Ἰάβε as meaning He who was and is and always exists. • (Pseudo-) (4th/5th century), (tetragrammaton) can be read Iaho; • (d. 457) writes Ἰαώ (Iao); he also reports that the say Ἰαβέ or Ἰαβαί (both pronounced at that time /ja'vε/), while the Jews say Ἀϊά (Aia).

(The latter is probably not יהוה but אהיה Ehyeh = 'I am ' or 'I will be', which the Jews counted among the names of God.) • (died 708), Jehjeh; • (died 420) speaks of certain Greek writers who misunderstood the Hebrew letters יהוה (read right-to-left) as the Greek letters ΠΙΠΙ (read left-to-right), thus changing YHWH to pipi. A window featuring the Hebrew tetragrammaton יְהֹוָה in, Vienna Peshitta [ ] The ( translation), probably in the second century, uses the word 'Lord' ( ܡܳܪܝܳܐ, pronounced moryo) for the Tetragrammaton. Vulgate [ ] The (Latin translation) made from the Hebrew in the 4th century CE, uses the word ('Lord'), a translation of the Hebrew word Adonai, for the tetragrammaton. The Vulgate translation, though made not from the Septuagint but from the Hebrew text, did not depart from the practice used in the Septuagint.

Thus, for most of its history, Christianity's translations of the Scriptures have used equivalents of Adonai to represent the tetragrammaton. Only at about the beginning of the 16th century did Christian translations of the Bible appear with transliterations of the tetragrammaton. Usage in religious traditions [ ] Judaism [ ]. Main article: Especially due to the existence of the, the tradition found in, and ancient Hebrew and Greek texts, biblical scholars widely hold that the tetragrammaton and other names of God were spoken by the ancient and their neighbours.: 40 Some time after the destruction of, the spoken use of God's name as it was written ceased among the people, even though knowledge of the pronunciation was perpetuated in rabbinic schools. The Talmud relays this occurred after the death of (either or his great-great-grandson ). Calls it, and says that it is lawful for those only whose ears and tongues are purified by wisdom to hear and utter it in a holy place (that is, for priests in the Temple). In another passage, commenting on Lev.

15 seq.: 'If any one, I do not say should against the Lord of men and gods, but should even dare to utter his name unseasonably, let him expect the penalty of death.' Rabbinic sources suggest that the name of God was pronounced only once a year, by the high priest, on the. Others, including, claim that the name was pronounced daily in the of the in the priestly of worshippers (Num. 27), after the daily sacrifice; in the, though, a substitute (probably 'Adonai') was used. According to the, in the last generations before the fall of, the name was pronounced in a low tone so that the sounds were lost in the chant of the priests.

Since the destruction of in 70 CE, the tetragrammaton has no longer been pronounced in the liturgy. However the pronunciation was still known in in the latter part of the 4th century. Verbal prohibitions [ ] The vehemence with which the utterance of the name is denounced in the suggests that use of Yahweh was unacceptable in rabbinical Judaism. 'He who pronounces the Name with its own letters has no part in the world to come!' Such is the prohibition of pronouncing the Name as written that it is sometimes called the 'Ineffable', 'Unutterable', or 'Distinctive Name'. Prescribes that whereas the Name written 'yodh he waw he', it is only to be pronounced 'Adonai'; and the latter name too is regarded as a holy name, and is only to be pronounced in prayer.

Thus when someone wants to refer in third person to either the written or spoken Name, the term HaShem 'the Name' is used; and this handle itself can also be used in prayer. The added vowel points () and marks to the manuscripts to indicate vowel usage and for use in ritual chanting of readings from the in in. To יהוה they added the vowels for ' Adonai' ('My Lord'), the word to use when the text was read.

While 'HaShem' is the most common way to reference 'the Name', the terms 'HaMaqom' (lit. 'The Place', i.e. 'The Omnipresent') and 'Raḥmana' (Aramaic, 'Merciful') are used in the mishna and, still used in the phrases 'HaMaqom y'naḥem ethḥem' ('may The Omnipresent console you'), the traditional phrase used in sitting and 'Raḥmana l'tzlan' ('may the Merciful save us' i.e. 'God forbid'). Written prohibitions [ ] The written tetragrammaton, as well as six other names of God, must be treated with special sanctity. They cannot be disposed of regularly, lest they be desecrated, but are usually put in long term storage or buried in Jewish cemeteries in order to retire them from use. Similarly, it is prohibited to write the tetragrammaton (or these other names) unnecessarily.

To guard the sanctity of the Name sometimes a letter is substituted by a different letter in writing (e.g. יקוק), or the letters are separated by one or more hyphens. Some Jews are stringent and extend the above safeguard by also not writing out other names of God in other languages, for example writing 'God' in English as 'G-d'. However this is beyond the letter of the law. Kabbalah [ ]. See also: and tradition holds that the correct pronunciation is known to a select few people in each generation, it is not generally known what this pronunciation is.

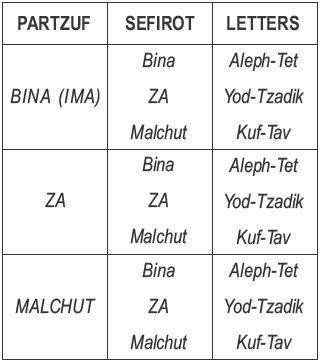

In late kabbalistic works the tetragrammaton is sometimes referred to as the name of Havayah— הוי'ה, meaning 'the Name of Being/Existence'. This name also helps when one needs to refer specifically to the written Name; similarly, 'Shem Adonoot', meaning 'the Name of Lordship' can be used to refer to the spoken name 'Adonai' specifically. [ ], says that the tree of the tetragrammaton 'unfolds' in accordance with the intrinsic nature of its letters, 'in the same order in which they appear in the Name, in the mystery of ten and the mystery of four.' Namely, the upper cusp of the Yod is and the main body of Yod is and; the first Hei is; the Vav is and the second Hei is. It unfolds in this aforementioned order and 'in the mystery of the four expansions' that are constituted by the following various spellings of the letters: ע'ב/ `AV: יו'ד ה'י וי'ו ה'י, so called '`AV' according to its value ע'ב=70+2=72.

ס'ג/ SaG: יו'ד ה'י וא'ו ה'י, gematria 63. מ'ה/ MaH: יו'ד ה'א וא'ו ה'א, gematria 45.

ב'ן/ BaN: יו'ד ה'ה ו'ו ה'ה, gematria 52. Luzzatto summarises, 'In sum, all that exists is founded on the mystery of this Name and upon the mystery of these letters of which it consists. This means that all the different orders and laws are all drawn after and come under the order of these four letters. This is not one particular pathway but rather the general path, which includes everything that exists in the in all their details and which brings everything under its order.' Another parallel is drawn [ ] between the four letters of the tetragrammaton and the: the י is associated with, the first ה with, the ו with, and final ה with. A tetractys of the letters of the Tetragrammaton adds up to 72. There are some [ ] who believe that the and its mysteries influenced the early.

A Hebrew tetractys in a similar way has the letters of the tetragrammaton (the four lettered name of God in Hebrew scripture) inscribed on the ten positions of the tetractys, from right to left. It has been argued that the Kabbalistic, with its ten spheres of emanation, is in some way connected to the tetractys, but its form is not that of a triangle. The occult writer says: 'The is assigned to Kether; the to Chokmah; the two-dimensional to Binah; consequently the three-dimensional naturally falls to Chesed.' (The first three-dimensional solid is the.) The relationship between geometrical shapes and the first four is analogous to the geometrical correlations in tetractys, shown above under Pythagorean Symbol, and unveils the relevance of the Tree of Life with the tetractys. Samaritans [ ] The shared the taboo of the Jews about the utterance of the name, and there is no evidence that its pronunciation was common Samaritan practice.

However includes the comment of, 'for example those Kutim who take an oath' would also have no share in the, which suggests that Mana thought some Samaritans used the name in making oaths. (Their priests have preserved a liturgical pronunciation 'Yahwe' or 'Yahwa' to the present day.) As with Jews, the use of Shema (שמא 'the Name') remains the everyday usage of the name among Samaritans, akin to Hebrew 'the Name' (Hebrew השם 'HaShem'). Christianity [ ]. The tetragrammaton as represented in stained glass in an 1868 Episcopal Church in Iowa It is assumed that early inherited from Jews the practice of reading 'Lord' where the tetragrammaton appeared in the Hebrew text, or where a tetragrammaton may have been marked in a Greek text. Gentile Christians, primarily non-Hebrew speaking and using Greek texts, may have read 'Lord' as it occurred in the Greek text of the and their copies of the. This practice continued into the Latin where 'Lord' represented the tetragrammaton in the Latin text. In 's Tetragrammaton-Trinity diagram, the name is written as 'Ieve'.

At the Reformation, the used 'Jehova' in the German text of Luther's Old Testament. Christian translations [ ] As mentioned above, the (Greek translation), the (Latin translation), and the ( translation) use the word 'Lord' ( κύριος, kyrios, dominus, and ܡܳܪܝܳܐ, moryo respectively). Use of the Septuagint by Christians in polemics with Jews led to its abandonment by the latter, making it a specifically Christian text. From it Christians made translations into,, and other languages used in and the, whose liturgies and doctrinal declarations are largely a cento of texts from the Septuagint, which they consider to be inspired at least as much as the Masoretic Text. Within the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Greek text remains the norm for texts in all languages, with particular reference to the wording used in prayers. The Septuagint, with its use of Κύριος to represent the tetragrammaton, was the basis also for Christian translations associated with the West, in particular the, which survives in some parts of the liturgy of the, and the.

Christian translations of the Bible into English commonly use 'L ORD' in place of the tetragrammaton in most passages, often in (or in all caps), so as to distinguish it from other words translated as 'Lord'. • In the (1864) a translation of the New Testament by Benjamin Wilson, the name Jehovah appears eighteen times. • The (1949/1964) uses 'Yahweh' eight times, including. • The (1966) uses 'Yahweh' in 6,823 places in the Old Testament. • The (NT 1961, OT 1970) generally uses the word 'L ORD' but uses 'J EHOVAH' several times. For examples of both forms, see Exodus Chapter 3 and footnote to verse 15. • The (1973/1978/1983/2011) generally uses 'the L ORD,' though in, the tetragrammaton is thrice translated 'I A M.'

In the Old Testament, when immediately preceded by אֲדֹנָי ( Adonai), the two words are translated 'the Sovereign L ORD.' • The (1985) uses 'Yahweh' in 6,823 places in the Old Testament. • The (1954/1987). At the AB says 'but by My name the Lord [Yahweh—the redemptive name of God] I did not make Myself known to them.' 'Jehovah' or 'Lord'. • The (1862/1898) (Version) – 'Jehovah' since • The (1999/2002) uses 'Yahweh' over 50 times, including.

• The (WEB) (1997) [a Public Domain work with no copyright] uses 'Yahweh' some 6837 times. • The (1996/2004) uses 'Yahweh' ten times, including. The Preface of the New Living Translation: Second Edition says that in a few cases they have used the name Yahweh (for example 3:15; 6:2–3).

• Rotherham's (1902) retains 'Yahweh' throughout the Old Testament. • The (in progress) retains 'Yahweh' throughout the Old Testament. • The (1611) – Jehovah appears seven times, i.e. Four times as ' JEHOVAH',;;, and three times as a part of Hebrew place-names;;. • Note: Elsewhere in the KJV, 'L ORD' is generally used.

But in verses such as;;, where this practice would result in 'Lord L ORD' (Hebrew: Adonay JHVH) or 'L ORD Lord' ( JHVH Adonay) the KJV translates the Hebrew text as 'Lord G OD' or 'L ORD God'. In the New Testament, when quoting, the all-caps L ORD for the Tetragrammaton appears four times, where the ordinary word 'Lord' also appears:,, and. • The (1901) uses 'Jehovah' in 6,823 places in the Old Testament.

• The (1961/1984/2013), published by the, uses 'Jehovah' in 7,216 places in both the and; 6,979 times in the Old Testament and 237 in the New Testament—including 70 of the 78 times where the New Testament quotes an Old Testament passage containing the Tetragrammaton, where the Tetragrammaton does not appear in any extant Greek manuscript. • the (1981) used by adherents of the Church of God (Seventh Day) inserts the name Yahweh in the Old and New Testament. • The (2011) uses 'Jehovah' in 6,973 places and 'Jah' in 50 places in the Old Testament. In addition, Jehovah appears in parentheses in 128 places in the New Testament wherever the New Testament quotes an Old Testament verse as a gloss (cross reference), totalling to 7,151 places in all.

• The (2012) uses 'Yahweh' throughout the Old Testament. • (1985) uses 'Jehovah' in 6,866 places in the Old Testament.

• The (1999) uses 'Jehovah' in 6,841 places in the Old Testament. • The (1890) by John Nelson Darby renders the Tetragrammaton as Jehovah 6,810 times.

• (1972) by Steven T. Byington, published by the Watchtower Bible and Tract Society, renders the Tetragrammaton as 'Jehovah' throughout the Old Testament over 6,800 times. • The (2011,2014) by Ann Spangler uses 'Yahweh' throughout the Old Testament. Eastern Orthodoxy [ ] The considers the Septuagint text, which uses Κύριος (Lord), to be the authoritative text of the Old Testament, and in its liturgical books and prayers it uses Κύριος in place of the tetragrammaton in texts derived from the Bible.: 247–248 Catholicism [ ].

Representation of the with the 10 in each, as successively smaller concentric circles, derived from the light of the Kav after the Suspicions aroused by the facts that the Zohar was discovered by one person, and that it refers to historical events of the post- period while purporting to be from an earlier time, caused the authorship to be questioned from the outset. Joseph Jacobs and Isaac Broyde, in their article on the Zohar for the 1906, cite a story involving the Kabbalist, who is supposed to have heard directly from the widow of de Leon that her husband proclaimed authorship by Shimon bar Yochai for profit: A story tells that after the death of Moses de Leon, a rich man of Avila named Joseph offered Moses' widow (who had been left without any means of supporting herself) a large sum of money for the original from which her husband had made the copy. She confessed that her husband himself was the author of the work. She had asked him several times, she said, why he had chosen to credit his own teachings to another, and he had always answered that doctrines put into the mouth of the miracle-working Shimon bar Yochai would be a rich source of profit. The story indicates that shortly after its appearance the work was believed by some to have been written by Moses de Leon. However, Isaac evidently ignored [ ] the woman's alleged confession in favor of the testimony of Joseph ben Todros and of Jacob, a pupil of, both of whom assured him on oath that the work was not written by de Leon.

Issac's testimony, which appeared in the first edition (1566) of Sefer Yuchasin, was censored from the second edition (1580) and remained absent from all editions thereafter until its restoration nearly 300 years later in the 1857 edition. Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan notes that Isaac evidently did not believe her, since Isaac quotes the Zohar as authored by Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai in a manuscript in Rabbi Kaplan's possession. This leads him to hypothesize that 's wife sold the original manuscript, as parchment was very valuable, and was embarrassed by the realization of its high ancient worth, leading her to claim it was written by her husband. Rabbi Kaplan concludes saying this was the probable series of events. The Zohar spread among the Jews with remarkable swiftness.

Scarcely fifty years had passed since its appearance in Spain before it was quoted by many, including the mystical writer and. Certain Jewish communities, however, such as the, (Western Sefardic or ), and some Italian communities, never accepted it as authentic. Late Middle Ages [ ] By the 15th century, its authority in the Spanish Jewish community was such that drew from it arguments in his attacks against, and even representatives of non-mystical Jewish thought began to assert its sacredness and invoke its authority in the decision of some ritual questions.

In Jacobs' and Broyde's view, they were attracted by its of man, its doctrine of, and its ethical principles, which they saw as more in keeping with the spirit of than are those taught by the philosophers, and which was held in contrast to the view of Maimonides and his followers, who regarded man as a fragment of the universe whose immortality is dependent upon the degree of development of his active intellect. The Zohar instead declared Man to be the lord of the, whose immortality is solely dependent upon his morality. Conversely, (c.1458 – c.1493), in his Bechinat ha-Dat endeavored to show that the Zohar could not be attributed to Shimon bar Yochai, by a number of arguments. Main article: Tikunei haZohar, which was printed as separate book, includes seventy commentaries called ' Tikunim' (lit. Repairs) and an additional eleven Tikkunim. In some editions Tikunim are printed that were already printed in the Zohar Chadash, which in their content and style also pertain to Tikunei haZohar.

Each of the seventy Tikunim of Tikunei haZohar begins by explaining the word ' Bereishit' (בראשית), and continues by explaining other verses, mainly in parashat Bereishit, and also from the rest of. And all this is in the way of, in commentaries that reveal the hidden and mystical aspects of the Torah. Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna are similar in style, language, and concepts, and are different from the rest of the Zohar. For example, the idea of the is found in Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna but not elsewhere, as is true of the very use of the term 'Kabbalah'. In terminology, what is called Kabbalah in → Tikunei haZohar and Ra'aya Meheimna is simply called razin (clues or hints) in the rest of the Zohar. In Tikunei haZohar there are many references to ' chibura kadma'ah' (meaning 'the earlier book'). This refers to the main body of the Zohar.

Parts of the Zohar: summary of Rabbinic view [ ] The traditional Rabbinic view is that most of the Zohar and the parts included in it (i.e. Those parts mentioned above) were written and compiled by Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, but some parts preceded Rashbi and he used them (such as Sifra deTzni'uta; see above), and some parts were written or arranged in generations after Rashbi's passing (for example, after Rashbi's time are occasionally mentioned).

However, aside from the parts of the Zohar mentioned above, in the Zohar are mentioned tens of earlier sources that Rashbi and his Chevraya Kadisha had, and they were apparently the foundation of the Kabbalistic tradition of the Zohar. These include Sefer Raziel, Sifra de'Agad'ta, Sifra de'Adam haRishon, Sifra de'Ashmedai, Sifra Chakhmeta 'Ila'ah diVnei Kedem, Sifra deChinukh, Sifra diShlomoh Malka, Sifra Kadma'i, Tzerufei de'Atvun de'Itmasru le'Adam beGan 'Eden, and more. In the Jewish view this indicates more, that the teaching of the in the book of the Zohar was not invented in the period, but rather it is a tradition from ancient times that Rashbi and his Chevraya Kadisha used and upon which they built and founded their Kabbalah, and also that its roots are in the Torah that was given by to on.

Viewpoint and exegesis: Rabbinic view [ ] According to the Zohar, the moral perfection of man influences the ideal world of the; for although the Sefirot accept everything from the ( אין סוף, infinity), the Tree of Life itself is dependent upon man: he alone can bring about the divine effusion. This concept is somewhat akin to the concept of. The dew that vivifies the universe flows from the just. By the practice of virtue and by moral perfection, man may increase the outpouring of heavenly grace. Even physical life is subservient to virtue.

This, says the Zohar, is indicated in the words 'for the Lord God had not caused it to rain' ( 2:5), which means that there had not yet been beneficent action in heaven, because man had not yet been created to pray for it. The Zohar assumes four kinds of Biblical text, from the literal to the more mystical: • The simple, literal meaning of the text: • The allusion or hinted/allegorical meaning: • The rabbinic comparison through sermon or illustration and metaphor: Derash • The secret/mysterious/hidden meaning: Sod The initial letters of these words (P, R, D, S) form together the word ('paradise/orchard'), which became the designation for the Zohar's view of a fourfold meaning of the text, of which the mystical sense is considered the highest part. Academic views [ ] In Eros and Kabbalah, Moshe Idel (Professor of Jewish Mysticism, Hebrew University in Jerusalem) argues that the fundamental distinction between the rational-philosophic strain of Judaism and mystical Judaism, as exemplified by the Zohar, is the mystical belief that the Godhead is complex, rather than simple, and that divinity is dynamic and incorporates gender, having both male and female dimensions.

These polarities must be conjoined (have yihud, 'union') to maintain the harmony of the cosmos. Idel characterizes this metaphysical point of view as 'ditheism', holding that there are two aspects to God, and the process of union as 'theoeroticism'.

This ditheism, the dynamics it entails, and its reverberations within creation is arguably the central interest of the Zohar, making up a huge proportion of its discourse (pp. 5–56). Mention should also be made of the work of (Professor of Jewish Mysticism, New York University), who has almost single-handedly challenged the conventional view, which is affirmed by Idel as well. Wolfson likewise recognizes the importance of heteroerotic symbolism in the kabbalistic understanding of the divine nature. The oneness of God is perceived in androgynous terms as the pairing of male and female, the former characterized as the capacity to overflow and the latter as the potential to receive. Where Wolfson breaks with Idel and other scholars of the kabbalah is in his insistence that the consequence of that heteroerotic union is the restoration of the female to the male.

Just as, in the case of the original Adam, woman was constructed from man, and their carnal cleaving together was portrayed as becoming one flesh, so the ideal for kabbalists is the reconstitution of what Wolfson calls the male androgyne. Much closer in spirit to some ancient Gnostic dicta, Wolfson understands the eschatological ideal in traditional kabbalah to have been the female becoming male (see his Circle in the Square and Language, Eros, Being). Commentaries [ ] The first known commentary on the book of Zohar, 'Ketem Paz', was written by Rabbi Shimon Lavi of Libya. Another important and influential commentary on Zohar, 22-volume 'Or Yakar', was written by Rabbi of the Tzfat (i.e. Safed) kabbalistic school in the 16th century. The authored a commentary on the Zohar. Rabbi Tzvi Hirsch of wrote a commentary on the Zohar entitled Ateres Tzvi.

A major commentary on the Zohar is the Sulam written by Rabbi. A full translation of the Zohar into Hebrew was made by the late Rabbi Daniel Frish of Jerusalem under the title Masok MiDvash. Influence [ ] Judaism [ ] On the one hand, the Zohar was lauded by many rabbis because it opposed religious formalism, stimulated one's imagination and emotions, and for many people helped reinvigorate the experience of prayer. In many places prayer had become a mere external religious exercise, while prayer was supposed to be a means of transcending earthly affairs and placing oneself in union with God.

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, 'On the other hand, the Zohar was censured by many rabbis because it propagated many superstitious beliefs, and produced a host of mystical dreamers, whose overexcited imaginations peopled the world with spirits, demons, and all kinds of good and bad influences.' Many classical rabbis, especially Maimonides, viewed all such beliefs as a violation of Judaic principles of faith. Its mystic mode of explaining some commandments was applied by its commentators to all religious observances, and produced a strong tendency to substitute mystic Judaism in the place of traditional rabbinic Judaism. For example,, the Jewish Sabbath, began to be looked upon as the embodiment of God in temporal life, and every ceremony performed on that day was considered to have an influence upon the superior world. Elements of the Zohar crept into the liturgy of the 16th and 17th centuries, and the religious poets not only used the allegorism and symbolism of the Zohar in their compositions, but even adopted its style, e.g. The use of erotic terminology to illustrate the relations between man and God.

Thus, in the language of some Jewish poets, the beloved one's curls indicate the mysteries of the Deity; sensuous pleasures, and especially intoxication, typify the highest degree of divine love as ecstatic contemplation; while the wine-room represents merely the state through which the human qualities merge or are exalted into those of God. In the 17th century, it was proposed that only Jewish men who were at least 40 years old could study Kabbalah, and by extension read the Zohar, because it was believed to be too powerful for those less emotionally mature and experienced.

Neo-Platonism [ ]. This section needs expansion.

You can help. (December 2010) Founded in the 3rd century CE by, The tradition has clear echoes in the Zohar, as indeed in many forms of mystical spirituality, whether Jewish, Christian or Muslim (see,, and ). The concept of creation by successive of God in particular is characteristic of neoplatonist thought.

In both Kabbalistic and Neoplatonist systems, the Logos, or Divine Wisdom, is the primordial archetype of the universe, and mediates between the divine idea and the material world. For example, the neoplatonist describes the Logos in terms of the 'One beyond being'. This primordial unity then, though self-complete, overflows with potency and from this power creates the manifold world beneath it. This downward movement from unity to multiplicity he calls Procession.

The reverse process of Reversion is then the lower lifeforms, such as humanity, ascending back toward God through spiritual contemplation. Jewish commentators on the Zohar expressly noted these Greek influences. Christian mysticism [ ]. This section possibly contains. Please by the claims made and adding. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (February 2015) () According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, 'The enthusiasm felt for the Zohar was shared by many Christian scholars, such as,,, etc., all of whom believed that the book contained proofs of the truth of.

They were led to this belief by the analogies existing between some of the teachings of the Zohar and certain Christian dogmas, such as the fall and redemption of man, and the dogma of the, which seems to be expressed in the Zohar in the following terms: 'The Ancient of Days has three heads. He reveals himself in three archetypes, all three forming but one. He is thus symbolized by the number Three. They are revealed in one another. [These are:] first, secret, hidden 'Wisdom'; above that the Holy Ancient One; and above Him the Unknowable One. None knows what He contains; He is above all conception.

He is therefore called for man 'Non-Existing' [ Ayin]' (Zohar, iii. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, 'This and other similar doctrines found in the Zohar are now known to be much older than Christianity, but the Christian scholars who were led by the similarity of these teachings to certain Christian dogmas deemed it their duty to propagate the Zohar.' However, fundamental to the Zohar are descriptions of the absolute Unity and uniqueness of God, in the Jewish understanding of it, rather than a trinity or other plurality. One of the most common phrases in the Zohar is ' raza d'yichuda 'the secret of his Unity', which describes the Oneness of God as completely indivisible, even in spiritual terms. A central passage, (introduction to 17a), for example, says: Elijah opened and said: 'Master of the worlds! You are One, but not in number. You are He Who is Highest of the High, Most Hidden of the Hidden; no thought can grasp You at all.And there is no image or likeness of You, inside or out.And aside from You, there is no unity on High or Below.

And You are acknowledged as the Cause of everything and the Master of everything.And You are the completion of them all. And as soon as You remove Yourself from them, all the Names remain like a body without a soul.All is to show how You conduct the world, but not that You have a known righteousness that is just, nor a known judgement that is merciful, nor any of these attributes at all.Blessed is forever, amen and amen! The meaning of the, according to the kabbalists, has extremely different connotations from ascribing validity to any compound or plurality in God, even if the compound is viewed as unified. In Kabbalah, while God is an absolutely simple (non-compound), infinite Unity beyond grasp, as described in by, through His Kabbalistic manifestations such as the and the (Divine Presence), we relate to the living dynamic Divinity that emanates, enclothes, is revealed in, and incorporates, the multifarious spiritual and physical plurality of Creation within the Infinite Unity. Creation is plural, while God is Unity. Kabbalistic theology unites the two in the paradox of human versus Divine perspectives.

The spiritual role of is to reach the level of perceiving the truth of the paradox, that all is One, spiritual and physical Creation being nullified into absolute Divine Monotheism. Ascribing any independent validity to the plural perspective is idolatry.

Nonetheless, through the of God, revealing the concealed mystery from within the Divine Unity, man can perceive and relate to God, who otherwise would be unbridgably far, as the supernal Divine emanations are mirrored in the mystical Divine nature of man's soul. The relationship between God's absolute Unity and Divine manifestations, may be compared to a man in a room - there is the man himself, and his presence and relationship to others in the room. In Hebrew, this is known as the Shekhinah. It is also the concept of God's Name - it is His relationship and presence in the world towards us. The Wisdom (literally written as Field of Apples) in kabbalistic terms refers to the Shekhinah, the Divine Presence. The Unknowable One (literally written as the Miniature Presence) refers to events on earth when events can be understood as natural happenings instead of God's act, although it is actually the act of God.

This is known as perceiving the Shekhinah through a blurry, cloudy lens. This means to say, although we see God's Presence (not God Himself) through natural occurrences, it is only through a blurry lens; as opposed to miracles, in which we clearly see and recognize God's presence in the world.

The Holy Ancient One refers to God Himself, Who is imperceivable. (see Minchas Yaakov and anonymous commentary in the Siddur Beis Yaakov on the Sabbath hymn of Askinu Seudasa, composed by the Arizal based on this lofty concept of the Zohar).

Within the descending of Creation, each successive realm perceives Divinity less and apparent independence more. The highest realm -Emanation, termed the 'Realm of Unity', is distinguished from the lower three realms, termed the 'Realm of Separation', by still having no self-awareness; absolute Divine Unity is revealed and Creation is nullified in its source. The lower three Worlds feel progressive degrees of independence from God. Where lower Creation can mistake the different Divine emmanations as plural, Atziluth feels their non-existent unity in God. Within the appearance of Creation, God is revealed through various and any plural numbers. God uses each number to represent a different supernal aspect of reality that He creates, to reflect their comprehensive inclusion in His absolute Oneness: 10, 12, 2 forms of, in Keter, 4 letters of the, 22 letters of the, 13, etc.

All such forms when traced back to their source in God's, return to their state of absolute Oneness. This is the consciousness of Atziluth. In Kabbalah, this perception is considered subconsciously innate to the, rooted in Atzilut. The souls of the Nations are elevated to this perception through adherence to the, that bring them to absolute Divine Unity and away from any false plural persepectives. There is an alternative notion of three in the Zohar that are One, 'Israel, the Torah and the Holy One Blessed Be He are One.' Norton Ghost 9 Download Full.

From the perspective of God, before in Creation, these three are revealed in their source as a simple (non-compound) absolute Unity, as is all potential Creation from God's perspective. In Kabbalah, especially in, the communal divinity of Israel is revealed Below in the righteous Jewish leader of each generation who is a collective soul of the people. In the view of Kabbalah, however, no Jew would worship the supernal community souls of the Jewish people, or the Rabbinic leader of the generation, nor the totality of Creation's unity in God itself, as Judaism innately perceives the absolute Monotheism of God.

In a Kabbalistic phrase, one prays 'to Him, not to His attributes'. As Kabbalah sees the Torah as the Divine blueprint of Creation, so any entity or idea in Creation receives its existence through an ultimate lifeforce in Torah interpretation. However, in the descent of Creation, the Tzimtzum constrictions and impure side of false independence from God results in distortion of the original vitality source and idea. Accordingly, in the Kabbalistic view, the non-Jewish belief in the Trinity, as well as the beliefs of all religions, have parallel, supernal notions within Kabbalah from which they ultimately exist in the process of Creation. However, the impure distortion results from human ascription of false validity and worship to Divine manifestations, rather than realising their nullification to God's Unity alone. In normative Christian theology, as well as the declaration of the, God is declared to be 'one'. Declarations such as 'God is three' or 'God is two' are condemned in later counsels as entirely and.

The beginning of the essential declaration of belief for Christians, the (somewhat equivalent to Maimonides' 13 principles of Faith), starts with the Shema influenced declaration that 'We Believe in One God.' Like Judaism, Christianity asserts the absolute monotheism of God. Unlike the Zohar, Christianity interprets the coming of the Messiah as the arrival of the true immanence of God. Like the Zohar the Messiah is believed to be the bringer of Divine Light: 'The Light (the Messiah) shineth in the Darkness and the Darkness has never put it out', yet the Light, although being God, is separable within God since no one has seen God in flesh: 'for no man has seen God.' It is through the belief that Jesus Christ is the Messiah, since God had vindicated him by raising him from the dead, that Christians believe that Jesus is paradoxically and substantially God, despite God's simple undivided unity.

The belief that Jesus Christ is 'God from God, Light from Light' is assigned as a mystery and weakness of the human mind affecting and effecting our comprehension of him. The mystery of the Trinity and our mystical union with the Ancient of Days will only be made, like in the Zohar, in the new, which is made holy by the Light of God where people's love for God is unending. Zohar study (Jewish view) [ ] Who Should Study Tikunei haZohar. This section possibly contains. Please by the claims made and adding. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed.

(February 2015) () Despite the preeminence of Tikunei haZohar and despite the topmost priority of Torah study in Judaism, much of the Zohar has been relatively obscure and unread in the Jewish world in recent times, particularly outside of Israel and outside of groups. Although some rabbis since the debacle still maintain that one should be married and forty years old in order to study Kabbalah, since the time of there has been relaxation of such stringency, and many maintain that it is sufficient to be married and knowledgeable in and hence permitted to study Kabbalah and by inclusion, Tikunei haZohar; and some rabbis will advise learning Kabbalah without restrictions of marriage or age. In any case the aim of such caution is to not become caught up in Kabbalah to the extent of departing from reality. Rabbinic Accolades; the Importance of Studying Tikunei haZohar Many eminent rabbis and sages have echoed the Zohar's own urgings for Jews to study it, and have and urged people in the strongest of terms to be involved with it. To quote from the Zohar and from some of those rabbis: ' Vehamaskilim yavinu/But they that are wise will understand' (Dan.

12:10) – from the side of, which is the Tree of Life. Therefore it is said, ' Vehamaskilim yaz'hiru kezohar haraki'a'/And they that are wise will shine like the radiance of the sky' (Dan. 12:3) – by means of this book of yours, which is the book of the Zohar, from the radiance ( Zohar) of Ima Ila'ah (the 'Higher Mother', the higher of the two primary that develop from Binah) [which is] teshuvah; with those [who study this work], trial is not needed. And because Yisrael will in the future taste from the Tree of Life, which is this book of the Zohar, they will go out, with it, from Exile, in a merciful manner, and with them will be fulfilled, ' Hashem badad yanchenu, ve'ein 'imo El nechar/Hashem alone will lead them, and there is no strange god with Him' (Deut. — Zohar Vol 1, p.

28a Rabbi said the following praise of the Zohar's effect in motivating performance, which is a main focus in: It is [already] known that learning the Zohar is very, very mesugal [capable of bringing good effects]. Now know, that by learning the Zohar, desire is generated for all types of study of the holy Torah; and the holy wording of the Zohar greatly arouses [a person] towards service of Hashem Yitbarakh.

Namely, the praise with which it praises and glorifies a person who serves Hashem, that is, the common expression of the Zohar in saying, ' Zaka'ah/Fortunate!' Regarding any mitzvah; and vice-versa, the cry that it shouts out, 'Vai!' Etc., ' Vai leh, Vai lenishmateh/Woe to him! Woe to his soul!' Regarding one who turns away from the service of Hashem — these expressions greatly arouse the man for the service of the Blessed One. — Sichot Haran #108 English translations [ ] • • Berg, Michael: Zohar 23 Volume Set- The Kabbalah Centre International.

Full 23 Volumes English translation with commentary and annotations. •, Nathan Wolski, & Joel Hecker, trans. The Zohar: Pritzker Edition (12 vols.) Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004-2017. • Matt, Daniel C. Zohar: Annotated and Explained.

Woodstock, Vt.: SkyLights Paths Publishing Co., 2002. (Selections) • Matt, Daniel C.

Zohar: The Book of Enlightenment. New York: Paulist Press, 1983. (Selections) • Scholem, Gershom, ed. Zohar: The Book of Splendor. New York: Schocken Books, 1963.

(Selections) • Sperling, Harry and Maurice Simon, eds. The Zohar (5 vols.).

London: Soncino Press. • Tishby, Isaiah, ed. The Wisdom of the Zohar: An Anthology of Texts (3 vols.). Translated from the Hebrew by David Goldstein. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

• Shimon Bar Yochai. Sefer ha Zohar (Vol. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 English)., 2015 See also [ ].